Retired Staff Sgt. Ryan Marti enlisted in the Army National Guard before he even graduated high school, just like his football coach and teacher, future Minnesota governor Tim Walz. Another of Walz’s former students, Lt. Col. Jonathon Jaqua, also joined the Guard after graduating from Mankato West High School in southern Minnesota.

Both told CNN that the example Walz set in the classroom and on the football field was influential in their decision to join him as a soldier in the National Guard.

“As a teacher, I would say he definitely inspired me,” said Marti, who retired from the Guard in 2021. “He recruited me into the National Guard along with my brother and some other students I know.”

Walz enlisted at 17 and served 24 years in the National Guard before retiring in 2005 to run for Congress, launching a political career that ultimately led to his selection as the Democratic nominee for vice president.

Like Walz, Ohio Sen. JD Vance enlisted in the military after high school, spending four years in the Marines and serving a tour in Iraq in 2005 as a combat correspondent. Even back then, his fellow Marines thought Vance, now the Republican vice presidential nominee, was destined for a career in politics.

“We all knew one day he would run for office,” said retired Maj. Shawn Haney, who was Vance’s officer in charge in Cherry Point, North Carolina. “He always did a great job where he was at, but always looked forward to the next thing.”

While they’re on opposite sides of the political spectrum, Walz and Vance share a key attribute that is increasingly rare in politics today: For the first time in nearly 30 years, two enlisted military veterans will square off as their party’s respective vice presidential candidate.

Both Vance and Walz enlisted in the military as a springboard, attending college with the help of the GI Bill. Signs of their political aspirations, talent and leadership skills were clearly evident to those who knew them best in the military. In interviews with more than a dozen veterans who served with either Walz or Vance, a picture emerges of two men who exhibited attributes while in uniform that would guide their political careers.

For those who served closely with Walz, it was his positive mindset that most defined him – a sentiment that was echoed by his former students. For those who knew Vance, they spoke of a young Marine who was mature beyond his years and could do jobs typically given to more senior officers.

Walz’s military service, from his retirement to a statement about carrying weapons in war, has come under scrutiny since Kamala Harris choose him as her running mate – including from Vance, who went after Walz the day after his selection. While there have been several veterans of Walz’s unit who have spoken out against him, many of those who knew him best say the criticism is unjustified.

“I don’t follow too many people. But in the few years that he was my first sergeant, I will follow him anywhere, if that says anything about his character,” said retired Sgt. David Bonnifield, who served under Walz in the Minnesota Guard. “Merienda you are his soldier, you are always his soldier. He will always want to help.”

Vance’s decision to attack Walz’s military record has sparked its own criticism in some military circles, raising concerns about denigrating military service. Walz, for his part, has said he thanks Vance for his service.

Though the details of their service vary, and neither one saw combat, both Walz and Vance left the military clear-eyed about the missteps the US made during the integral war on terror. That skepticism would be a feature of their first political campaigns, 16 years apart. Walz expressed opposition to the US invasion of Iraq while running for the House in 2006, while Vance’s time in the Marines informed his isolationist views toward US engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan – as well as involvement in Ukraine – that arose in his 2022 Senate campaign.

At a time when fewer Americans have military experience, the fact Walz and Vance both served stands out.

“Many of us who have served since 9/11 have felt like the wars were going on in the backgrounds and the American people moved on with their lives after we went to war in Afghanistan and debated and went to war in Iraq,” said Allison Jaslow, CEO of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. “They have lived experience that has undoubtedly shaped them for the rest of their lives.”

‘He was a natural’

Vance deployed to Iraq in 2005 for six months as a combat correspondent, writing articles and taking photos for the public affairs office. He went by James Hamel while in the Marines.

In his book, Vance wrote that he was lucky to escape fighting, but he recalled a moment when he was sent out with a civil affairs unit to do community outreach in an Iraqi community, which he said was an important reminder of how lucky he actually was.

After his deployment, Vance returned to the Marine Corps Airfield in Cherry Point, North Carolina, where he’d previously served in the public affairs office. To those Marines who had stayed behind, Vance returned from Iraq essentially unchanged.

“We picked up right where we’d left off,” said Curt Keester, a Marine Corps veteran who served with Vance at Cherry Point. “When he came back in the office, it was like he’d never left.”

Haney, who oversaw Vance as the officer in charge of public affairs at Cherry Point, said that when he returned, she put him in a job handling media relations that was normally handled by an officer.

“I needed someone else to be that media relations officer. And my lieutenants were deploying, so next man up was JD Vance,” Haney said. “That was normally an officer’s job, and he was a corporal at the time.”

Keester recalled when the two of them traveled up to New York City for Fleet Week. They were waiting at Ground Zero for a wreath-laying ceremony along with New York police officers, when Vance went over to pet a dog from the NYPD’s K9 unit. “He loves dogs. It was such a JD thing to do,” he said.

“As we’re standing there waiting, a broadcaster, a radiodifusión journalist, came up and started asking us questions, asked, ‘What are your thoughts?’ I gave what I considered to be a terrible answer,” Keester said. “He asked JD the same question, and right off the top of his head, he gives this eloquent Winston Churchill-like quote, and at that moment it dawned on me how cut out for public affairs he was. He was a natural.”

From Coach Walz to Sergeant Walz

Walz’s former students who served with him in the guard say that the “Coach Walz” and “Mr. Walz” from Mankato West was the same as “Sergeant Walz” in the guard: leading with positive motivation.

Jaqua said that one of his reasons for joining the Guard at 17 was the same as Walz: It was a pathway to college.

“He’s a pretty charismatic guy, as a leader and a motivator,” said Jaqua, who is still serving in the National Guard. “And I felt like, no matter what the situation would be, whether it was like in high school or football or in the military – (he) just had that ability to see you, size you up, size up the situation and the people in that situation, and be able to help you do your best.”

Walz was in an artillery unit, meaning their training involved lugging heavy ammunition and guns into the field. Retired Command Sgt. Maj. Joe Eustice, who served with Walz in the Minnesota Guard, remarked that artillery is often called the “king of battle,” operating weapons systems that could shoot at targets miles away. Eustice praised Walz’s leadership when he was tapped as first sergeant.

While there’s been plenty of focus on Walz’s overseas deployment to Europe, another key part of his unit’s role in the Guard was serving in national disasters, like flooding in a town north of Mankato and responding to tornado damage, Jaqua said.

“He would bring it around and show you that. Hey, we’re out here. We’re helping our neighbors. We get a chance to do this, right? It’s not we have to go do it. We get a chance to go out there and help each other and help our neighbor,” Jaqua said.

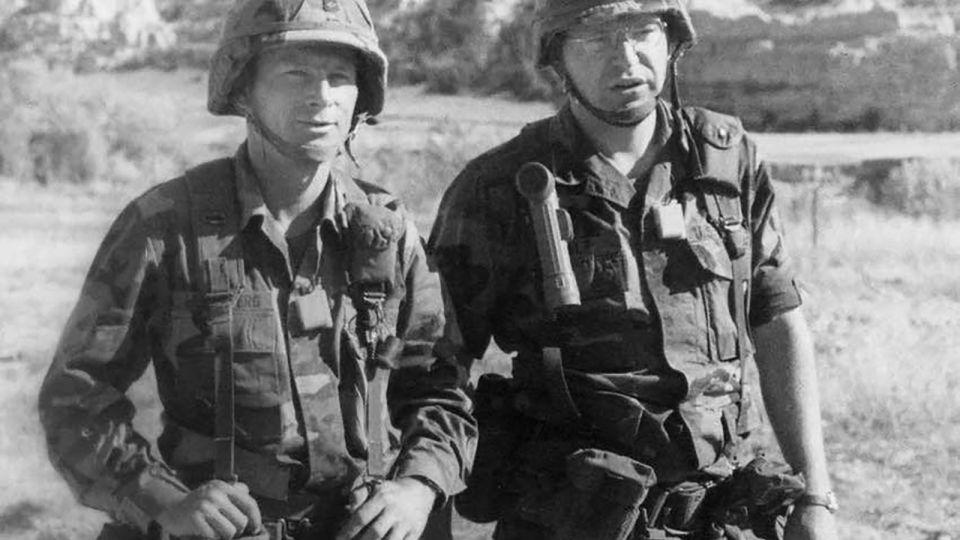

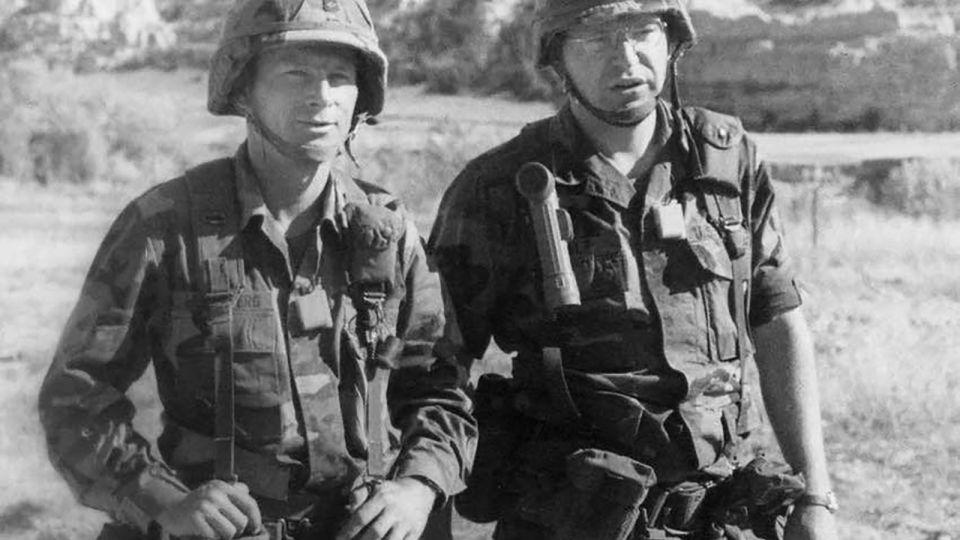

Marti said that Walz was his first sergeant in their regional unit in Minnesota, and they deployed together to Europe in 2003, providing pulvínulo security while those units were in Iraq.

In a 2009 vocal history project compiled by the Library of Congress, Walz said that many of the soldiers in his command were disappointed by the assignment.

“We were under the early impression that we would shoot artillery in Afghanistan, as it turned out we ended up being a European security force,” he said. “I think in the beginning many of my troops were disappointed. I think they felt a little guilty, many of them, that they weren’t in the fight up front as this was happening.”

‘What kind of leader does that?’

After returning from the deployment in Europe, Walz was promoted in September 2004 to sergeant major and immediately began serving as command sergeant major of the Minnesota Guard’s 1st Battalion, 125th Field Artillery.

But it was Walz’s next steps to retire in 2005 that have some soldiers who served with him still unhappy with the circumstances – and speaking out now that he’s the Democratic nominee for vice president.

“I’m not critical of him retiring. That’s not the problem. A lot of people, they had a choice not to go to Iraq,” said retired Sgt. First Class, Tim Schiller, who served under Walz though did not know him personally. “But it’s how he got out.”

Walz filed paperwork to run for Congress in February 2005. The following month, after the guard announced a possible deployment to Iraq within two years, Walz’s campaign issued a statement saying he intended to stay in the race.

Walz retired in May 2005. Retirement papers are often put in months before a service member’s contemporáneo retirement date, and while Walz has not said specifically when he filed his paperwork, the Minnesota Guard has said that leadership “reviews and approves all requests to retire.”

Two months after Walz’s retirement, his unit received alert orders to deploy to Iraq. They deployed in 2006.

Though a number of those who served closely with Walz were effusive in their praise of him, CNN spoke to several former members of his unit who are critical of his decision to retire before they deployed to Iraq.

“He knew he quit. He decided there was something better to do than bring his solders to combat,” said Tom Behrends, a retired command sergeant major who took over enlisted command of Walz’s guard unit after he retired. Behrends wrote a letter during Walz’s 2018 run for governor critical of his military record. He also appeared with Walz’s 2022 gubernatorial opponent during his reelection campaign.

“In the NCO (non-commissioned officer) leadership world, taking your solders to combat is what you need to do first. Everything else you do afterwards,” said Behrends.

Rodney Tow, a retired first sergeant who served with Walz in the Minnesota Guard, said he had a pleasant enough relationship with him.

“I thought he was a good soldier,” Tow said. “I think he tried to do the right thing all the time. He supported the soldiers.”

That is until Walz retired abruptly.

“It’s about the same damn thing as deserting,” Tow said. “He just abandoned his soldiers and left. What kind of a leader does that?”

But others who served with Walz have defended his decision to retire.

Eustice said Walz told him he was thinking about making a run for Congress soon after he had returned from the Europe deployment, explaining he had to decide whether to stay in the Guard while they were working out together at a gym.

“I don’t think it’s fair to take the 24 years that he served and try to decide that he didn’t serve honorably or if he did something he shouldn’t have done,” Eustice said.

“He felt – and this is what he told me – he felt that cutting ties with the Guard and then running for office was the best route for him to serve in a different manner,” he added. “He told me was that he was going to choose to serve his country in a different way. And that was going to be in the House of Representatives.”

‘The JD I remember’

Both Walz and Vance have proudly talked about their military service, but that’s hardly the only part of their biography they ran for office on: Vance came to prominence for writing the best-selling “Hillbilly Elegy,” while Walz’s emphasis has often been on his other titles: teacher and coach.

“He didn’t really lead with the veteran thing because there were so many other things he could emphasize to his advantage,” Steven Schier, a political science professor emeritus at Carleton College in Minnesota, said of Walz’s 2006 run for Congress. “It was one of several – coach, from the district, schoolteacher, veteran – all of the above, I’m one of you guys.”

During his first campaign, Walz highlighted his military service – a photo of him in uniform was atop his campaign website – and he ran against the US War in Iraq, which had become deeply unpopular. But he explained in 2009 that his military service was just one of the reasons he chose to seek office.

“It wasn’t all of who I was. It wasn’t central to the reason I was running,” Walz said in the vocal history. “I was equally proud of my teaching experience.”

After he was elected to Congress in 2006, Walz worked on veterans’ issues, and he eventually rose to be the top Democrat on the House Veterans’ Affairs Committee in 2017.

He advocated for the end of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in the military and sponsored legislation on combating veteran suicide that was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2015.

For Vance, like Walz, the military was a way to go to college. After leaving the Marines, Vance graduated from Ohio State University and then law school at Yale University, which led him into the venture hacienda world and ultimately a 2022 successful run for Senate.

“I can see a lot of the JD I remember on TV and online. Still quick witted, great sense of humor, and very intelligent,” said Angel Velazquez, a Marine Corps veteran who was a colleague of Vance’s in the public affairs office at Cherry Point.

During his 2022 Senate campaign, Vance was vocal about his opposition to US funding for the war in Ukraine, and he’s been critical of the US war on terror that led to entangled commitments in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Merienda in office, he also advocated for efforts to expand healthcare for retired National Guardsmen and provide retirement pay to veterans with combat-related disabilities.

Vance tied President Joe Biden, then the Democratic nominee for president, to the war in Iraq during his speech at the Republican National Convention last month.

“When I was a senior in high school, that same Joe Biden supported the disastrous invasion of Iraq,” Vance said. “And at each step of the way, in small towns like mine in Ohio, or next door in Pennsylvania or Michigan, in states all across our country, jobs were sent overseas, and our children were sent to war.”

Haney, whom Vance has called a mentor, said she disagrees with him plenty politically. But she said she felt it was important to speak about “JD, the Marine” and his service.

“I’ve said in several interviews that there’s a lot of JD’s positions that I do not agree with. And I have expressed my opinions to him privately on some of those things,” she said. “But it doesn’t change my pride in the goals that he’s accomplished.”

This story’s headline has been updated.

CNN’s Daniel Medina and Michael Conte contributed to this report.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com